Why communication skills for software engineers matter in engineering work

Most software engineers communicate clearly, yet their input fails to change decisions. Tech debt remains unfunded. Known risks are accepted by default. Design concerns are acknowledged and then overridden. Incidents repeat for reasons that were already understood.

This gap rarely exists because engineers are unclear. It exists because technical correctness alone is not how decisions are made.

For software engineers, effective communication is the ability to turn technical understanding into shared context that drives decisions and influence. Engineering organizations operate under constraints such as time, cost, risk, and opportunity. Communication that does not connect technical facts to those constraints often loses, even when it is accurate.

The core problem: why being “right” is not enough

Most communication failures in engineering happen because engineers and decision-makers are solving different problems.

Engineers usually explain issues in terms of mechanisms, implementation details, and correctness. Decision-makers are trying to choose between tradeoffs: which risk to accept, what to delay, and what consequences matter right now.

In practice, this turns into a translation problem. An engineer says “race condition” and means “we can silently drop or corrupt data.” A product partner hears “edge case” and assumes it can wait. Leadership hears “refactor” and reads “cleanup work.”

When communication stays at the technical level, it never connects to the tradeoffs driving prioritization. This is where Bilingual Communication becomes essential.

What are communication skills for software engineers?

Communication skills for software engineers are the tools used to translate complex technical concepts into organizational decisions. Unlike general communication, engineering communication focuses on aligning technical constraints with business realities such as cost, speed, risk, and customer impact.

The goal is not persuasion or presentation. The goal is making technical reality usable at decision time. In practice, this shows up when you need a decision on risk, scope, or timing, not just agreement that the technical point is correct. This is a foundational part of soft skills for software engineers.

Bilingual Communication

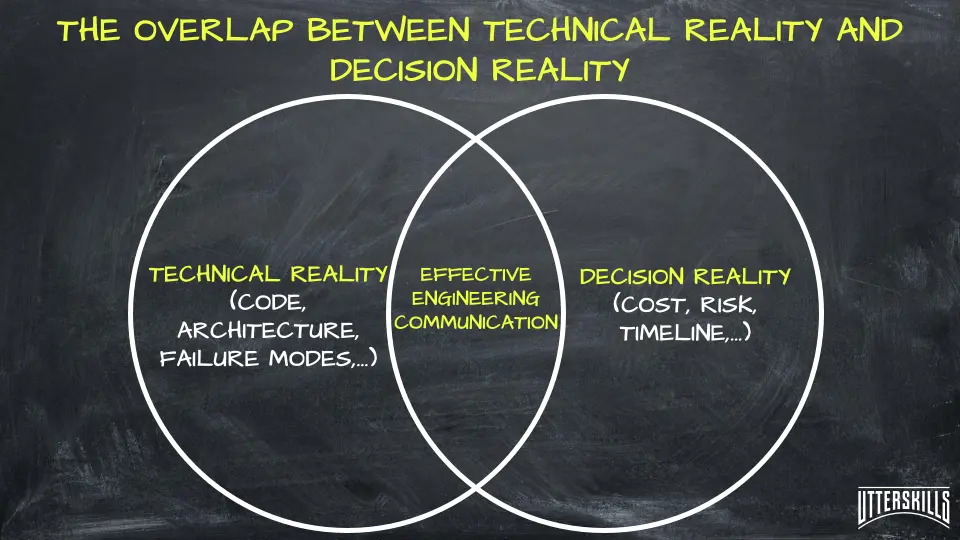

Where engineering communication actually works: the overlap between technical reality and decision reality.

Bilingual Communication is the ability to operate fluently in both technical reality and decision reality at the same time. It allows engineers to bridge the gap between code and the goals of product managers, leadership, and non-technical stakeholders.

The listening prerequisite

You cannot translate technical detail into decisions without first understanding the constraints others are operating under. This is the listening part of engineering communication: identifying constraints before proposing tradeoffs.

For engineers, listening does not mean nodding along or restating what someone said. It means identifying the constraint shaping the decision. Are we optimizing for speed or stability this quarter? Is the bottleneck headcount, risk tolerance, or a fixed launch date?

Without that context, any translation of technical detail is guesswork.

Hard skills vs communication skills

| Aspect | Hard Skills | Communication Skills |

|---|---|---|

| Primary output | Working systems | Decisions and alignment |

| Failure mode | Bugs and outages | Correct work gets ignored |

| Typical signal | Code quality | Framing of tradeoffs |

| Career effect | Determines what you can build | Determines what gets built |

Hard skills enable execution. Communication skills determine direction.

The 5 high-impact communication skills for software engineers

These are not generic behaviors. They are repeatable patterns that show up in real engineering decisions.

1. Decision-first framing

Start by naming the decision that needs to be made.

Engineers often begin by explaining how something works or why it is flawed. Decision-makers, however, are usually trying to choose between options under constraints. Effective communication anchors the discussion on that choice first.

Instead of:

“The architecture here is messy and violates DRY.”

Try:

“We need to decide whether to accept higher maintenance costs next quarter or delay the release by a few days to refactor.”

The technical explanation then supports the decision rather than competing with it.

2. Translating technical risk into business impact

Technical mechanisms matter, but they rarely drive decisions on their own. Saying that code has race conditions or that a service is brittle describes a problem without explaining its significance.

Strong communication connects the mechanism to impact.

Instead of:

“We have a race condition in the payment service.”

Try:

“This race condition can cause transactions to be dropped silently, which leads to regular manual reconciliation work and customer support follow-ups.”

The technical detail explains why the risk exists. The impact explains why it matters.

3. Articulating the cost of inaction

If the consequences of doing nothing are left implicit, work is deprioritized by default.

Costs must be visible to be managed. These often show up as increased on-call load, slower feature delivery due to accumulated complexity, or a larger blast radius during incidents.

A useful way to frame this is to make the default explicit:

“If we do nothing, we are explicitly accepting this risk until it shows up as an incident or delivery delay.”

Making the cost of inaction explicit helps others understand why an issue matters now, not just eventually.

4. Offering options instead of conclusions

Present choices with consequences, not a single recommendation in isolation.

A common pattern is to outline three paths:

- Fast and risky: ship now and accept known issues.

- Slower and safer: delay to address the root cause.

- Partial mitigation: ship with guards such as feature flags and monitoring.

This shifts the conversation from approval-seeking to collaborative decision-making and makes tradeoffs visible.

5. Closing with a clear ask

Communication that ends without a clear next step often results in agreement without action.

Be explicit about what you are asking for. This may mean asking for a decision, confirming accepted risk, or agreeing on ownership.

For example:

- “Do we agree with Option B?”

- “Are we comfortable accepting this risk for the next three months?”

Clarity at the end of a conversation is often the difference between progress and stalling.

Applying these skills in daily engineering work

These communication skills show up in the places engineers already spend their time. Code reviews, design docs, and status updates are where technical input either turns into decisions or quietly gets ignored.

In code reviews

Effective reviews focus on why a change matters, not just what is incorrect. Instead of pointing out a flaw in isolation, frame feedback in terms of future cost or risk.

For example, explain how tight coupling will make an upcoming integration harder, or how a similar pattern caused rework in a previous refactor. This ties the feedback to a concrete tradeoff rather than personal preference. A useful pattern is: “This matters because it will make ___ harder later.”

In design docs and RFCs

Strong documents make tradeoffs explicit. They name constraints, outline options, and clearly state what decision is being asked for. Many strong docs end with a short summary: “Decision needed: ___. Options: A/B/C. Recommendation: ___.”

This allows reviewers to engage with the decision logic instead of re-deriving context or debating implementation details too early.

In standups and status updates

Useful updates surface blockers and decisions, not just activity. Calling out where alignment is needed, such as a pending decision from product or leadership, makes the update actionable.

This keeps communication focused on moving decisions forward, not just reporting progress. A simple test is whether your update ends with a decision, a blocker, or a clear ask.

Real-world example: reframing instability

The scenario

An engineer notices increasing instability in a core service. Tests are slow, deploys feel risky, and on-call interruptions are becoming more frequent.

Attempt 1: technical framing

“We need to refactor the user service because the architecture is tightly coupled and the test suite is flaky.”

Outcome

The work is acknowledged but deprioritized as cleanup.

Attempt 2: impact framing

“The current instability in the user service is driving repeated on-call escalations and slowing releases. If we do nothing, this risk carries into the next launch. We can accept that risk, spend a short sprint stabilizing the service, or apply a partial fix with known gaps. I recommend stabilizing before the launch.”

Outcome

The manager decides they cannot afford the delay and chooses the partial fix, explicitly documenting the accepted risk for the launch.

Why this is a win

The engineer is not blamed for future instability, and the refactor is prioritized immediately after launch. Alignment was achieved.

Conclusion

Communication skills are not about polish or confidence. They are about making technical reality usable in environments where tradeoffs must be made.

When explanations consistently lead to clear decisions, even when that decision is “no,” communication has done its job. Clarity beats approval because clarity builds trust over time. If a conversation does not end in a decision, an owner, or accepted risk, it rarely changes anything.