Most Advice Assumes Control You Don't Have

Most time management advice assumes that individuals control their schedules and can decide when to focus. That assumption does not hold in most engineering roles.

Work arrives during implementation. Dependencies break without warning. Requests for input interrupt ongoing work. Estimates change when unknowns surface. These are not edge cases. They are the normal operating conditions of engineering teams.

If you plan as if these things will not happen, the plan will fail. The question is not how to eliminate them, but how to work in a way that does not collapse when they show up.

If this framing feels new, the reasons behind it are covered in: Time Management for Software Engineers: What Makes It Hard.

Planning When Estimates Will Be Wrong

Estimates fail because real systems contain things you cannot see until you touch them.

APIs behave differently than documented. Existing code relies on assumptions nobody wrote down. Performance characteristics only appear under production load. These are discoveries, not estimation mistakes.

Planning based on precise scope assumes none of this will happen.

| What Plans Assume | What Actually Happens |

|---|---|

| Work starts at sprint start | Work arrives mid-implementation |

| Scope is known upfront | Unknowns surface after starting |

| Tasks run independently | Dependencies block progress |

| Estimates reflect effort | Discoveries change the work |

| Time is evenly usable | Focus time is fragmented |

Planning fails when it assumes the left column will hold under real delivery conditions.

What actually works is planning for movement. That usually means working within time boxes and making assumptions explicit before starting.

In practice, that sounds like:

“I have three days. This part should fit. This part depends on the API behaving as expected. If that assumption breaks, it won't.”

I have seen teams avoid a lot of late-stage pressure simply by naming assumptions early and agreeing on what moves when one breaks. The plan does not become more accurate, but it becomes adjustable.

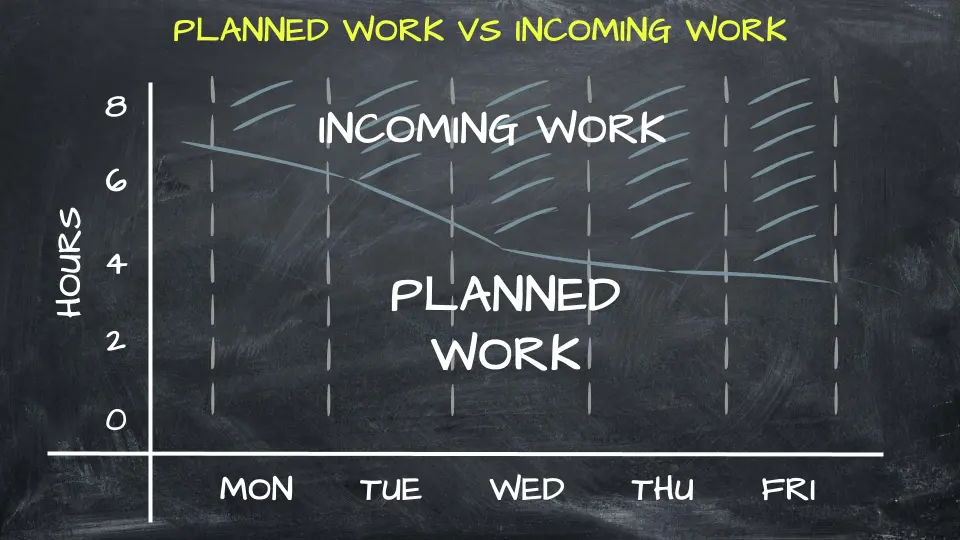

Incoming Work Changes Priorities, Even When It's Small

Overload rarely comes from one large assignment. It accumulates through small requests: a review here, a quick question there, a short pairing session that runs longer than expected.

Each one shifts priorities, even if nobody says so.

Incoming work includes reviews, questions, bugs, incidents, and coordination that wasn't in the original plan.

This is how it usually plays out. Mid-week, you are halfway through a feature. A teammate asks for a quick review. Then a message comes in about a flaky test. None of this feels big enough to escalate. By Friday, the original work is behind, and the conversation becomes “why didn't this get done” instead of “why did priorities change on Tuesday.”

I have seen this exact pattern repeat across teams where people were clearly competent and working hard, yet still ended the week under pressure.

The failure is not effort. It is silence.

| Situation | Silent Overload | Explicit Tradeoff |

|---|---|---|

| New request arrives | Work is added quietly | Existing work is named as delayed |

| Interruption mid-sprint | Engineer absorbs the cost | Priority change is discussed |

| Deadline pressure | Quality drops unnoticed | Scope or risk is adjusted openly |

| Missed delivery | Blame appears late | Constraint was visible early |

Both paths do the same work; only one makes the tradeoff visible before it is too late.

When new work arrives, the most effective response is not to ask how to fit it in. It is to ask which existing work will be delayed as a result, and to ask that question out loud to the person making the request.

I have asked this question in real planning conversations, and it consistently changed the discussion from personal effort to shared prioritization.

Work in Progress Is the Real Tax

Carrying multiple active tasks at once makes everything slower.

Each task requires maintaining its own mental context. Each switch incurs a reload cost. Each partially finished item becomes another place for work to stall.

This is why five things that are “almost done” feel heavier than one thing that is clearly blocked.

The version that scales is simple and uncomfortable: finish work before starting new work. Pause blocked tasks instead of juggling them. Treat “blocked” as a state, not a failure.

On teams I have worked with, limiting work in progress was the single most effective change for reducing constant background pressure.

Protecting Focus Without Eliminating Collaboration

Interruptions are unavoidable. Restarting complex work repeatedly is what causes damage.

Design, debugging, and non-trivial changes require holding a detailed mental model of the system. When that model is dropped, rebuilding it takes time.

The practical response is not isolation. It is making availability predictable.

In practice, this often means answering messages in defined windows instead of continuously, and being explicit about when you are interruptible and when you are not. On teams I've worked with, simply batching Slack and email reduced the number of context resets far more than any focus technique ever did.

Batching asynchronous communication, using visible focus blocks, and defining a clear escalation path for urgent issues all serve the same purpose: reducing how often deep work is interrupted and restarted.

This keeps collaboration intact while avoiding the constant reset cost that kills progress.

Making Time Debt Explicit

When time pressure increases, shortcuts appear. Tests are shortened. Refactors are postponed. Reviews are rushed.

These decisions are sometimes reasonable. They become dangerous when their future cost is invisible.

For example, skipping a test on a fragile integration might save an hour today. Two weeks later, when the same code path breaks under a slightly different input, you lose half a day re-deriving assumptions you could have locked in with that test.

The fix is not avoiding shortcuts entirely. It is naming their cost at the moment they are taken.

“Skipping this saves time now, but it will slow every future change here.”

Time management matters here because it determines when these tradeoffs are acknowledged, not whether they exist.

Conclusion

Engineering work will always involve interruptions, uncertainty, and competing demands. None of this can be solved through better discipline or tighter schedules.

What changes outcomes is when constraints and tradeoffs become visible. If they surface early, scope and priorities can still change. If they surface late, the remaining options are rushed work or increased risk.

If there is one practice worth applying immediately, it is this:

When new work arrives, ask which existing work will be delayed. Ask it early, ask it out loud, and write the answer down.

That single habit removes most of what engineers experience as “bad time management.”

Author Quote

Software Engineer & Tech Lead

“Once you accept that interruptions, uncertainty, and shifting priorities are normal, the problem changes. This article focuses on how engineers work inside those constraints without relying on discipline or heroics.”

- Florian Schmidt