The Problem Engineers Actually Have

Most engineers are not disorganized. They are overloaded.

A normal week includes:

- planned feature work

- unplanned bugs or incidents

- code reviews

- meetings where decisions are made

- messages asking for help or quick input

- helping unblock other people

All of this competes for the same limited time.

When more work arrives than can be finished, something has to give. If no one decides what moves or what drops, the tradeoffs still happen. They just happen late and without discussion.

That is what most engineers experience as “bad time management.”

Why Productivity Advice Misses the Point

Most time management advice assumes:

- you control your schedule

- tasks can be paused and resumed cheaply

- interruptions are minor

- priorities stay stable

Engineering work does not behave like that.

Debugging, design, and non-trivial changes require holding a mental model of the system. That model includes call paths, data flow, failure cases, and assumptions in the code. When you are interrupted, that model is dropped.

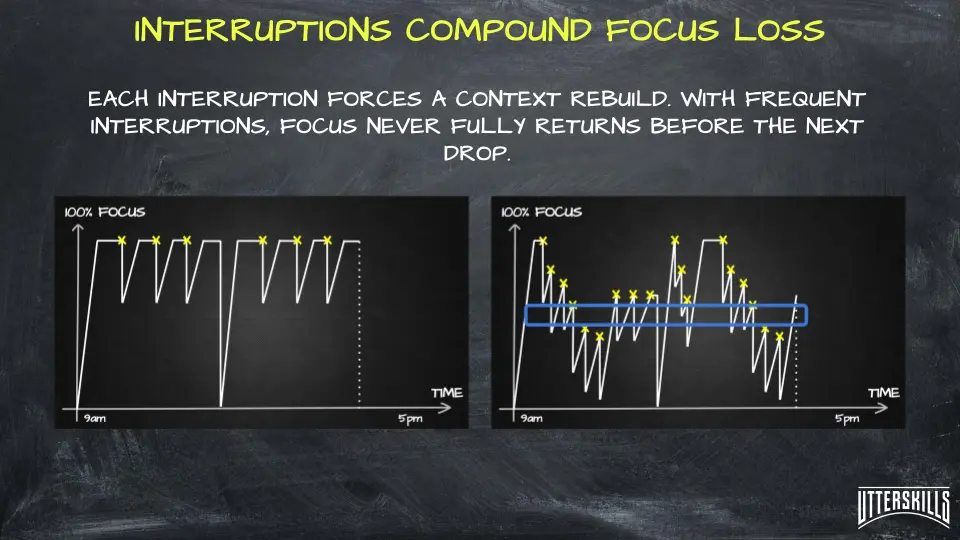

Reloading it is not free. For most engineers, it takes 15–30 minutes to fully get back into context after a real interruption, and that cost repeats every time.

| Interrupts per day | Time lost to context reload |

|---|---|

| 1 | ~15–30 minutes |

| 2 | ~30–60 minutes |

| 4 | ~60–120 minutes |

| 6 | ~90–180 minutes |

Each interruption triggers a context reload. Over a day, these costs add up.

Left: recovery completes between interruptions. Right: interruptions arrive before recovery finishes, so average focus stays lower.

In practice, the problem usually is not focus or discipline. It is the cost of being interrupted and having to rebuild context over and over again.

Your Calendar Is Not Your Capacity

A calendar shows availability, not usable time.

A single 30-minute meeting at 2 PM does not cost 30 minutes. It splits what could have been a 4–6 hour block into fragments that are too small for deep work. The afternoon is effectively gone for anything that requires sustained thinking.

This is why managers operate in hourly blocks and engineers usually cannot. It is not a matter of preference. It is cognitive load. A Maker's Schedule does not survive random meetings.

Planning work as if all hours were interchangeable is a reliable way to create plans that fall apart quickly.

Context Switching Compounds Quickly

Working on one thing at a time is relatively cheap.

Working on several things at once is expensive.

Each additional task adds:

- another mental model to maintain

- another context reload cost

- another place for work to stall

This is why having five things “almost done” often feels worse than having one thing clearly blocked. The overhead grows faster than the task count.

Starting new work often feels like progress, but it is finishing work that actually frees capacity and reduces load.

Small Requests Create an Invisible Backlog

Most overload does not come from one large task. It comes from many small ones:

- quick questions

- short reviews

- “can you take a look at this?” messages

Each one changes priorities, even if no one says so explicitly.

Over time, an invisible backlog forms. It is visible to the engineer doing the work, but invisible to everyone else. By the time delivery pressure becomes obvious, the backlog already exists.

At that point, the remaining options are rushing, cutting quality, or working longer hours.

This directly supports the “invisible backlog” and “capacity ≠ calendar” arguments.

Where engineering time actually goes

| Type of work | Visible in planning | Typical impact |

|---|---|---|

| Planned feature work | Yes | Predictable |

| Meetings | Yes | Fragmentation |

| Code reviews | Sometimes | Context reload |

| “Quick questions” | No | Priority drift |

| Helping unblock others | No | Lost focus |

| Incidents / urgent fixes | Partially | Forced switches |

Much of the time that reduces capacity is not explicitly planned or tracked.

Why Estimation Breaks Down

Estimates fail for predictable reasons.

Real systems contain unknowns that only appear after work starts. Common examples include:

- APIs that behave differently than documented

- existing code with hidden assumptions

- performance that looks fine in staging and fails in production

- third-party libraries with edge cases or bugs

You cannot estimate things you do not know exist.

These are discoveries, not estimation mistakes, and treating them as estimation failures usually hides the real issue.

Plans that assume no discoveries will happen tend to be fragile by design.

How Time Pressure Turns Into Risk

When time runs out, tradeoffs happen automatically:

- scope is reduced quietly

- tests are skipped or shortened

- reviews are rushed

- fixes are postponed

These are not bad decisions in isolation. They are what happens when decisions are made too late, under pressure.

Time management matters because it determines when tradeoffs are made and whether they are visible to others.

What More Experienced Engineers Do Differently

More experienced engineers do not have more hours. They tend to force prioritization earlier.

Junior pattern:

- Accepts a full sprint of work

- Starts implementing

- Discovers blockers mid-sprint

- Scrambles to compensate

More experienced pattern:

- Reviews work before starting

- Calls out dependencies and risks immediately

- States what fits and what does not, in writing

- Pushes prioritization decisions back to planning

The difference is not speed. It is when these conversations happen.

This kind of early constraint-surfacing is one of the few non-technical skills that actually changes outcomes. We describe it alongside related patterns in our overview of soft skills for software engineers.

This is where skills beyond code start to matter. Not as polish, but as the ability to make constraints visible while there is still room to adjust.

One Shift That Helps Immediately

You do not need new tools to apply this.

When new work arrives, instead of asking:

“How can I fit this in?”

Ask:

“What moves if I take this on?”

Ask this question to the person giving you the work and make the tradeoff explicit. Even if nothing changes, the constraint is now visible, which already prevents a lot of silent overload.

Conclusion

Time management for software engineers is not about efficiency. It is about visibility.

Work will keep arriving. Interruptions will happen. Unknowns will surface.

The difference is largely about timing. You can deal with these realities early, while options still exist, or deal with them later, when the only option left is overtime.

This article explains why time management breaks down in engineering work. The follow-up focuses on how individual engineers operate inside those constraints without relying on discipline or heroics: Time Management for Software Engineers: How Work Actually Gets Done.